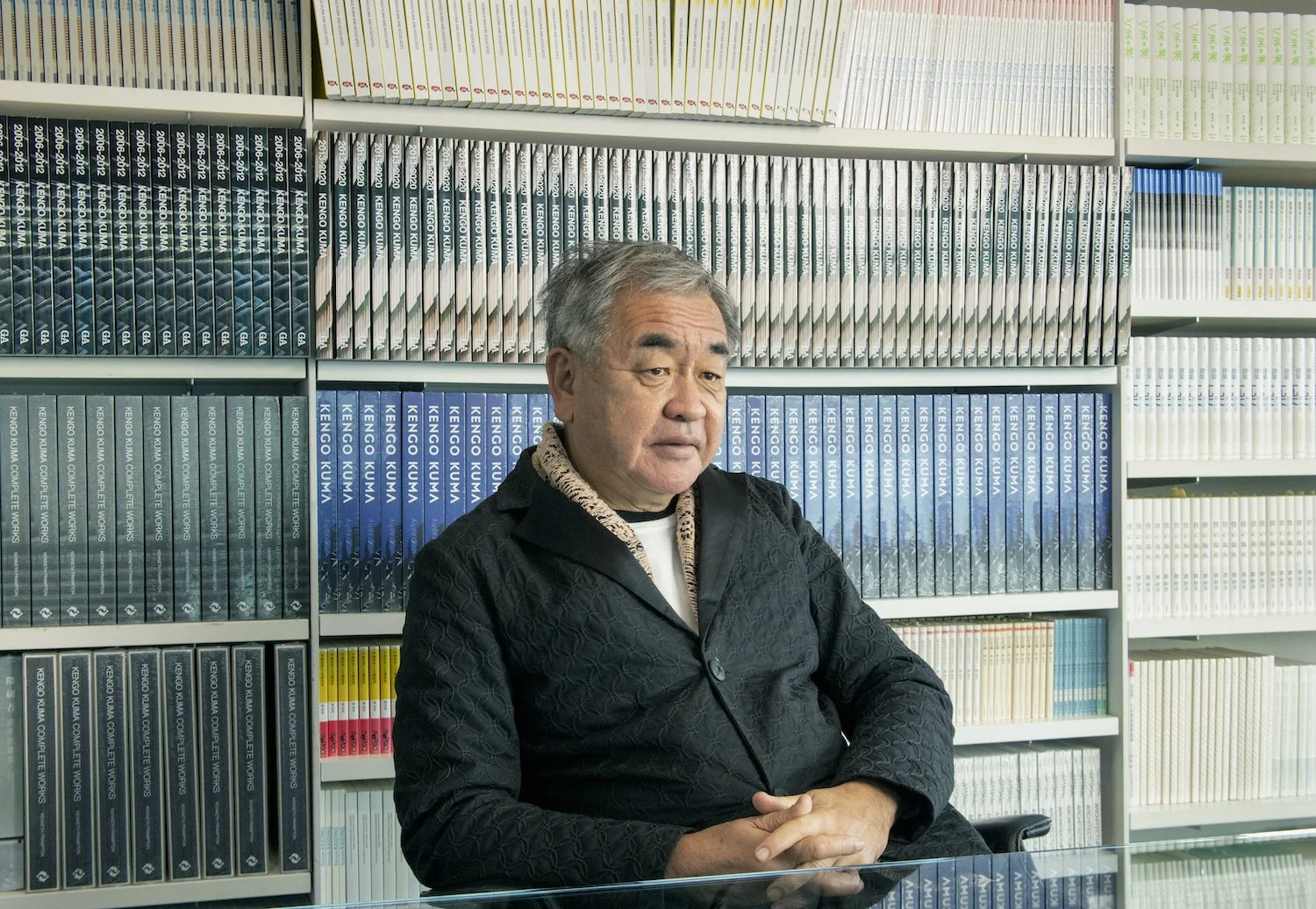

Kengo Kuma in his office ©TOKI

We first spoke with one of Japan’s architectural legends, Kengo Kuma a few years back, when we dove deep into his work, the development of Japanese architecture in a rapidly global society, and his views on the preservation of Japanese culture. You can read the interview here.

Since then, the world has taken a rapid and unexpected turn. So recently, we sat down with Kuma again, this time to hear his take on architectural shifts amid the global pandemic, and his vision for the future of Japanese architecture. Within countless prestigious awards for his approach to architecture in a post-industrial society in his book, we were curious to see what sort of vision for the future he had in a post-pandemic society.

©TOKI

Of course, even within the pandemic Kuma and his firm, Kengo Kuma & Associates, have maintained their architectural ideology that believes in architecture that melds with its cultural and environmental surroundings, as well as gentle, human-scaled buildings. They continue to search for new sustainable materials to replace the traditional, western builds of concrete and steel.

But amidst a life-altering event that has forever changed humanity’s perspective on human connection and spatial design, the value of reconnection with nature and sustainable living has never been more profound. Kuma believes this is a value that resonates deeply with Japanese design.

“You can feel nature in Japanese architecture. The breeze of the wind, the sun of daybreak. You can feel many different elements of nature in one building. It goes beyond just the shape of the building, but the emotions and expressions of nature. This coexistence is something you cannot find anywhere else in the world”.

Moving away from steel and concrete, Kuma places care into highlighting the use of raw materials from nature, especially local raw materials.

“For me, the building should melt into the landscape.”

Ashigara Station Civic Center, a recently completed build in Ashigara, a station facing Mount Fuji in Oyama, Shizuoka is an ode to the usage of local raw materials. The station has a roof that soars upwards, leading the visitors’ eyes to Mount Fuji. The deep eaves of the roof are supported by parabolic interlocking wooden lumber pieces. Kengo Kuma and Associates worked specifically with Fujiyama Kintokizai, an Oyama local wood pine supplier, a material symbolic of regional economic revitalization and sustainable building practices.

Nezu Museum ©Nezu Museum

Another prime example of this idea of synthesis between building and landscape is the Nezu Museum located in Tokyo, Japan. Kuma wanted the museum to be linked naturally with its surroundings by the shade from the gentle slope of the roof, located between the busy commercial area and the woods. The building is not fenced in from the city. Rather, it is open to it through the bamboo thicket, an attempt for a museum as an urban design. It is a wonderful expression of a building working harmoniously with its environment.

Another element of nature that can always be seen featured in Kuma’s work is the relationship between shadow and light. “Asian buildings have always characteristically had the element of shadows created by big sunroofs. This is my starting point for my interest.”

Approach to Nezu Museum ©Nezu Museum

When talking about the Nezu Museum, it is also a wonderful example of another defining feature of Japanese architecture, the element of omotenashi.

“Japanese hospitality, or omotenashi, is not one of words, but of sequences”

At Nezu Museum, People go along the bamboo under the deep eave, like a passage from the lively town to the forest of beauty. Just like winding paths in the gardens leading to traditional Japanese tearooms, visitors need to make turns to change their mood and end the flow from Meiji Shrine and Omotesando. The space is not a design of shape, but a design of sequences and flows.

As Kuma explains, “The Japanese purposely choose to show their respect and hospitality through actions and feelings rather than words.”

But omotenashi is also not just about the exterior design of the building, but also the interior and everything that the guest experiences. Because of this, Kuma and his associates also work in the design of interior pieces.

Kuma shows us his mock-ups ©TOKI

Kuma pauses for a second before reflecting. “True Japanese beauty is the combination of interior, landscape, and objects.”

Objects are an important part of the entire experience. Every aspect must be designed, because just by having the object there, the person feels something, hears something.

In Shinto, Japan’s oldest indigenous religion, people believe that all objects have a soul. Kuma feels similarly. “Rocks, trees; I believe all objects have a sort of personality of their own.

This form of thinking is something I picked up while designing Japanese yards. It is a widely accepted view of objects for the lawn.”

For Kuma, the value of the physical experience cannot be replicated. “I want guests to feel moved, to feel empathy. Whenever there is a new project, I make sure to first physically go to the location myself, to walk inside, take note of what I see first and how I see it.”

When asked what space comes to mind as the epitome of omotenashi, Kuma was quick to answer. “The tea ceremony space. It is like making omotenashi into a tangible shape. It is a design that takes into account 100% of the guests’ actions. I don’t think a design with such high resolution exists anywhere else in the world.”

Because omotenashi is not something put into words, sometimes guests who are not attuned to small details will miss elements of the design, but to Kuma, this is not a problem. “Guests may only realize a small fraction of the omotenashi that we have designed in, but that is fine as well. Based on country or culture, each person will discover something different. That small discovery is what will stay in their hearts, and maybe even connect to them wanting to learn more about omotenashi”.

Ashigara Station - Ashigara Station Civic Center ©Kawasumi・Kobayashi Kenji Photograph Office

Ashigara Station - Ashigara Station Civic Center ©Kawasumi・Kobayashi Kenji Photograph Office

Shifting away from omotenashi, we asked Kuma about his perspective on the future of Japanese architecture. He explains that Japan’s original architecture was effectively destroyed after WWII, and the adaptation of the American model of architecture took place. However, Kuma believes that Japan is slowly starting to develop its own distinct style again. He sees Japanese architecture finally finding its place in the world alongside the shifting definitions of the city. With the pandemic, people have begun reflecting on what it means to live within a city. Kuma sees the current model of a city, with the skyscrapers and vast majority of space dedicated to cars, changing slowly but surely. Roads will shrink as we move more and more into a future where cars will not be our main source of transport, and high-rise buildings will disappear as people choose to live closer to nature.

Higashikawa, Hokkaido

Kuma and his associates are taking this to heart, building satellite offices all throughout Japan. “We built one in Higashikawa, Hokkaido. It is a building in the center of a vast field of nothingness. Or we also built one in Okayama. We started from an old existing building, and are now redesigning it to suit our needs. Our offices no longer need to exist in big cities, they can live in nature”.

In the future, Kuma intends to use these offices to gather inspiration in different locations. A particular current interest and inspiration is the use of kayabuki as a raw material. Kayabuki or kaya is the general term for the grass that thatches a roof. They are traditionally made from silver grass.

“There are plenty of buildings that use wood, but not many that make use of kayabuki. Kayabuki is an essential part of satoyama.”

Satoyama (里 – sato, or village; 山- yama, or mountain) is generally translated as “Japanese countryside”, however, it means something much deeper expressing the importance of this intersection of human society and nature. Rather than simply being a place distant from the urban centers, Satoyama are places where human presence is integrated in such a way that promotes the wellbeing of the natural landscapes rather than a desire to conquer it.

Silver grass fields play a major role in the Japanese rural ecosystem, and learning how to incorporate more of this native species into our architecture could be a major movement in sustainability.

Yusuhara Marche exterior ©Takumi Ota

“When I was in Okayama we explored a building made entirely from kayabuki. You often only find kayabuki used for thatched roofs, but by using it for the entire house, it maintains its integrity and the organic texture of the kayabuki can be felt more clearly.”

In 2010, Kuma worked on the Yusuhara Marche in Kochi, Japan. Working within the small rural town in the mountains, he learned from local traditions and used the kayabuki thatching as exterior walls to the building rather than the traditional roof. The thatched elements can be rotated to provide ventilation within the building. Kuma may be reflecting back to this build as he draws new inspiration for the use of sustainable, local materials in modern architectural builds.

For Kuma, his interests and curiosities shift often, and he finds himself drawn to many different ideas at different times. However, the most inspiring moments always come during the output process.

“I take in lots of information in the process of output. For example, if I am building something new, I will take lots of time to speak with the builders to get inspired and learn new things. The most important and interesting part of taking things in is being able to put something out into the world. It’s not like a school exam, where you learn just because you have to. You learn because you are passionate because you have the urge and desire to create value and meaning in the world”.

©TOKI

RESERVE AN architecture EXPERIENCE

READ OTHER ARTISAN STORIES